The Chimp Paradox is, without doubt, one of my favourite non-fiction books. I can say with confidence that ever since reading this book for the first time during University, I have used the model it lays out every single day. I recently finished my third full read through and am still picking up useful points I’d previously missed.

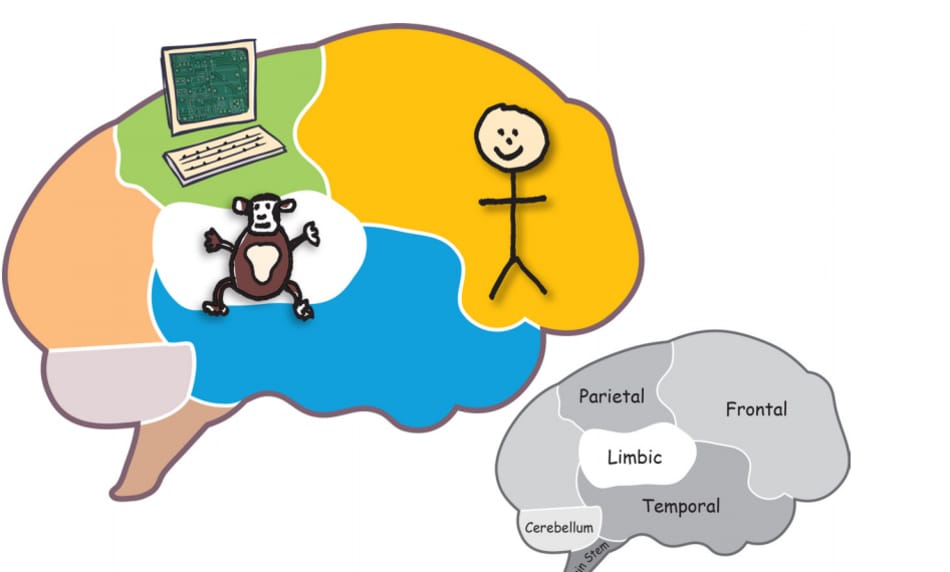

The Chimp Paradox by Professor Steve Peters is an excellent mind management tool that can help you understand the inner workings of your brain via the analogy that the emotional centre of your brain (the amygdala) is represented by a chimp whilst the rational part (frontal lobe) is your human.

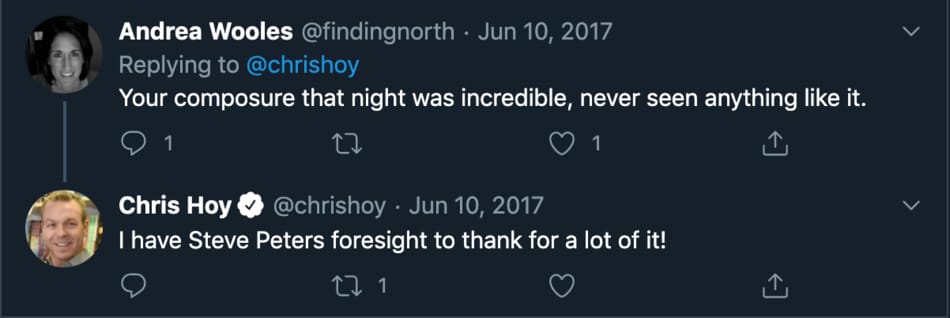

The author, Professor Steve Peters, is best known for his work in sports psychiatry – helping the likes of Ronnie O’Sullivan, Chris Hoy and Liverpool FC to great success in their respective sports. In each case, he taught them the contents of this book – the mental model for understanding yourself known as ‘The Chimp Paradox’.

The Chimp Paradox Summary

The Chimp Paradox starts by introducing a simplified mental model whereby the logical prefrontal cortex section of the brain is represented by the human and is who you truly are as a person. Meanwhile, the emotional centre, the limbic system – is represented by a strong, emotion-driven chimp who you must learn to manage.

Human = rational, logical part of your brain. The pre-frontal cortex. Your true personality.

Chimp = irrational, emotional part of your brain. The limbic system. Designed to keep you safe.

Humans, even when presented with what is obviously a logical choice, will often end up acting irrationally. If you think back, you can probably pinpoint a time where you have acted irrationally at the moment and later felt embarrassed by the way you’ve acted. This book explains that’s it’s not truly ‘you’ doing and saying these things, but rather, your chimp.

The human part of the brain is what helps you to think and act rationally and to thrive in a modern society whilst the chimp portion of the brain is more primitive, acting on feelings and emotions. Whilst it may sound like having a chimp is a chore, its role is actually essential, controlling the “fight, flight or freeze” reaction that keeps us safe in our daily lives.

The issue is, in a civilised society, you don’t want your emotional, sometimes irrational, chimp running the show. Steve Peters is quick to point out that many people mistake their feelings and emotions (their chimp) for their true personality (the human). Whilst different people are able to contain and manage their chimps to different degrees, this, the author argues, is not what makes up your actual personality.

The reason why we as humans often struggle to act rationally and unemotionally is because the chimp is roughly 5* stronger and much faster than the human within our brains. For example, let’s say you went into your kitchen and spotted a slice of cake. The rational human in you may say “I don’t need a slice of cake, it’s unhealthy” but an unmanaged chimp is much stronger and easily overpowers the human, giving all the reasons in the world why you should, in fact, eat the cake which you end up doing.

Whilst it may sound it, the chimp is not inherently good or bad and if managed well can be a huge source of advantage – for example, if you’re struggling to complete a work task, you could get your chimp on board via negotiating with it and telling yourself completing this task competently will likely result in compliments from your work colleagues. As soon as the chimp recognises the possibility of external validation, it will help the human part of your brain to complete the work task.

This is an example of managing your chimp so you can coexist successfully. The book goes on to lay out the below specific tactics for how to best manage your chimp:

Tactic #1 – distract the chimp

The first tactic discussed is to distract your chimp. Let’s say your chimp has become uneasy at the thought of giving a public speech right before you are due to go on stage. Clearly, you don’t have time in this situation to manage your chimp effectively using the strategies laid out below, so a short term solution can be to distract your chimp. For example, you may bargain with your chimp and say “once we’ve delivered this speech and done a good job, we can relax and order a pizza for dinner” – whilst this isn’t a long term solution, it’s an effective option every so often.

Another distraction tip I’ve used myself is to count to 10 before responding to situations in which you think your chimp might make an appearance. This gives the slower human part of the brain time to catch up and weigh in before the chimp reacts in an unfavourable way.

Tactic #2 – exercise and then box the chimp

This is the most effective tactic and the one that should be deployed as often as is needed before it starts to become second nature. When your chimp (emotional part of your brain) begins to react to something negatively, you should first exercise it in an appropriate location.

For example, let’s say you’ve got upset over poor perceived treatment by a colleague – the first step would be to go somewhere private and exercise the chimp by allowing it to express its feelings, regardless of how irrational they may sound. This may be alone or even with somebody else who you trust but never with the subject of who is causing these emotions as the thoughts and feelings of the chimp could be damaging.

After your chimp has unloaded all of the perceived issues with the work colleague, it will begin to tire itself out. At this point, the rational human side of the brain can step back in and ‘box’ the chimp with facts and truth to counter the emotional point of view.

The key point here is that you need to learn to live with and manage your chimp rather than fight against it as this is a biological fight you simply can not win due to the limbic systems (chimp) power within your brain.

This is often misinterpreted as a sign that you can not be held responsible for the actions of your chimp but this is a fallacy – the book gives the example that the chimp is akin to a pet dog, you are responsible for its actions as the owner and can’t simply say ‘the dog ripped up your furniture, not me’ to absolve yourself of responsibility.

The third part of the brain, the computer, is also introduced which is described as a storage area throughout the brain for your programmed thoughts and beliefs.

This can be both a blessing and a curse; whilst we can develop helpful autopilot behaviours which override the chimps emotional response, we also have what Steve Peter’s refers to as ‘Gremlins’ which are long-held destructive beliefs such as “I’m not good enough to try that”.

About the author

The Chimp Paradox is written (and narrated) by Professor Steve Peters who is a Psychiatrist specialising in the functioning of the human mind. Steve Peters is highly qualified in his field holding degrees and postgraduate qualifications in medicine, mathematics, education, medical education, sports medicine and psychiatry.

This CV has allowed Steve Peters to work with some of the biggest names in Sport including the GB Olympics team, the English national football team, Liverpool Football Club and the most decorated snooker player to ever play the game; Ronnie O’Sullivan.

Ronnie O’Sullivan credits Steve Peters for “making me the player I am today” whilst Sir Chris Hoy, British Olympic cycling hero throughout the 2000-2012 period, also speaks highly of his work, suggesting his famous composure can be attributed to Steve Peters work.

Not all famous British athletes have looked upon Professor Peters so positively, Bradley Wiggins is alleged to have described the underlying theories of The Chimp Paradox as “a load of rubbish” whilst he was also criticised in the media following England Football’s disastrous Euro 2016 campaign, but generally speaking he is highly thought of within sports psychology.

Steve Peter’s has a number of other books published on similar topics with ‘My Hidden Chimp’ and ‘The Silent Guides’ being his other notable work.

What I liked about the Chimp Paradox

The first thing I liked about the Chimp Paradox was how intuitive and easy to understand the model is. Whilst the brain is a hugely complex organ that we still don’t fully understand, this book simplifies certain key parts and allows a layman such as myself to understand how the mind works in daily life and how to act in your own best interests.

I would describe myself as more of a logical rather than an emotional person; I am what the Myers Briggs personality test would call an ‘ISTJ’ (find out your personality type here).

The Chimp Paradox model suggests that the rational, human part of the brain is who you truly are whilst the emotional side is your chimp. I found this sentiment reassuring that human personalities are inherently rational rather than emotional in nature and that the emotional parts of our brain can be managed by the human part.

The final thing I liked about this book is how practical it is. Often books in the ‘self-help’ genre can be a little bit too high-level and theoretical so it was a pleasant surprise to have a book that explained its points with reference to real-life examples and gave practical exercises to work through to make sure you understand the content.

My favourite example was of a man who, whilst driving to work one morning, had a car dangerously pull out in front of him. The man spent the next 5 minutes of his journey beeping his horn, swearing and driving close behind the offending vehicle to exact revenge. Once the man arrived at work, he was still visibly annoyed and began to moan to his colleagues. Later that day, the man replied to an innocuous email rudely, still angry at what had transpired that morning.

Having read this book, it’s clear these actions are the work of the emotional chimp part of the brain rather than the logical human. The chimp in this situation is screaming within our brain that the idiot driver has put our lives in danger and we must make our feelings clear to anyone that will listen.

I’m no stranger to swearing at bad drivers myself, but having read this book, I can at least appreciate whilst doing it that this isn’t the rational part of my brain at work and that reacting in this way does nothing but further annoy me.

What I didn’t like about the Chimp Paradox

This is one of my favourite books so there isn’t a huge amount I didn’t like but if I had to pick out a few criticisms, it would be these:

For those into neurology, the model may be a bit overly simplistic and fail to show how the complex brain truly works. For me, this wasn’t a big issue as I was more interested in learning the model to manage my mind rather than understanding the science behind it. I think it could be made clearer in the book that this is a model and an analogy rather than how your brain truly operates but I can appreciate this is left down to the reader so as not to overcomplicate the key messages of the book.

The front 65% of the book is far superior to the remaining 35%. It seems a bit like Steve Peters fell into the classic non-fiction trap of having a great idea and then trying to write too many words on it to fill a word quota. Whilst the 2nd half of the book is still useful, interesting writing – the main value of The Chimp Paradox comes earlier in the book.

The final criticism is highly subjective but I found that Steve Peters narration within the audiobook was slightly grating to listen to, so I would recommend buying the paper version of this book. Of course, this is down to my subjective taste, but generally speaking, I think audio-book narrations should be left to professional narrators, not the original author.

My main takeaways from the Chimp Paradox

My main takeaways from The Chimp Paradox are:

- Your brain has an emotional centre ‘the chimp’, a logical centre ‘the human’ and a storage place for all automatic beliefs ‘the computer’.

- The chimp is not inherently good or bad but it is strong and must be nurtured and managed in order to live in a civilised society.

- The chimp can be managed by distracting it or exercising it until it’s worn out and then boxing it with logic and facts.

- The chimp is an evolutionary essential as it helps keep us safe and drives our other key needs via the fight, flight and freeze reactions.

- Your personality is the ‘human’ portion of your brain and whilst you are not responsible for the nature of the chimp, you are responsible for managing it.

Quote of the book

“Remember: you can’t use your Chimp as an excuse. If you had a dog and it bit someone, you couldn’t just say, ‘Sorry but it was the dog, not me.’ You are responsible for the dog and its actions. Likewise, you are totally responsible for your Chimp and its actions. So no excuses!”

Professor Steve Peters

Conclusion

This is one of my favourite non-fiction books of all time. Whilst the mental model may be overly simplistic for those with a deep interest in brain psychology, for me it was pitched at the perfect level. The book, which I’ve recently read for the 3rd time, has completely changed the way I frame my internal reactions to things that happen in everyday life.

Whilst I don’t claim to have a zen-like calm persona, using this book I have begun to avoid reacting to things emotionally via the ‘chimp brain’ and instead react more logically via the ‘human brain’ and whilst I continue to develop this skill, I have seen clear, tangible benefits so far.

As this blog is about financial independence and your personal finance, I have to link this book back into those themes. People who foster the ability to think and react logically and rationally will always do better financially than those who don’t. If you need evidence of this, read any book on the inconsistencies of humans investing within the stock market and how money is almost always lost on the back of irrational decision making; such as overconfidence or not properly weighing up risk and you’ll see what I mean.

To purchase this book on amazon (in any format) – head to this link.

Head over to my ‘TPP Recommends‘ page where you will see this book featured.

This article has been written by Luke Girling, ACA – a qualified Accountant and personal finance enthusiast in the UK. Please visit my ‘About‘ page for more information. To get in touch with questions or ideas for future posts, please comment below or contact me here.

Intriguing: I will have a look or listen

ought the book, utter garbage. All this book has done is make me more angry. I now have even less respect for psychology (which is a made up subject) than i did before.

Hi Paul, sorry you didn’t enjoy the book. What about it did you disagree with? As I say in the review, it’s not perfect but I found it a useful mental model for understanding our actions.