Learning double entry Accounting using the DEAD CLIC acronym is one of the cornerstones to developing your financial literacy. As a qualified Accountant I learnt this in a formal setting, but for most people, learning the fundamentals of double entry Accounting can be achieved simply by reading the rest of this post.

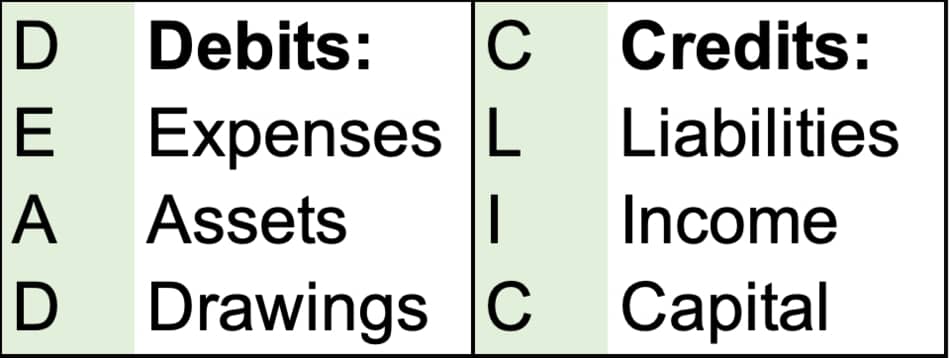

Double entry Accounting is a system whereby two bookkeeping entries are required for each transaction. The entries are made via debits & credits which can be remembered via the acronym DEAD CLIC which stands for Debits: expenses, assets, drawings and Credits: Liabilities, Income, Capital.

I’ve done my best to make sure that this post doesn’t fall in line with the common school of thought that “Accounting is boring”. But even if you do find this kind of thing tedious – the hard truth is that to become financially independent, you have to have basic financial literacy and that includes Accounting. For the fastest way to understand basic double entry Accounting, put aside 10 minutes to read the below.

How to use DEAD CLIC for double entry Accounting

Every single transaction a Company records, whether it be a sale, a purchase of a supplies for your business, a purchase of a building for your business to operate or paying your annual tax bill will involve posting two entries to your ledgers and ultimately your financial statements – hence the name ‘double entry Accounting’.

These two entries are known as debits and credits whereby for every transaction, you will post at least one debit and at least one credit which will overall net off to 0.

DEAD CLIC is a popular acronym which allows you to remember which balances to debit and which to credit when recording an Accounting transaction.

D (debit) – tells you to debit the ledger when you are posting an E (expense), A (asset) or D (drawing) i.e. if any of these things increase, you post a debit to the appropriate place. For example, if you incurred an electricity bill of £100, your expenses have increased by £100 and as such, you debit the profit and loss statement (more on this below) in the expenses account and you post a corresponding credit to your liabilities balance within the balance sheet.

C (credit) – tells you to credit the ledger when you are posting an L (liability), I (income) or C (capital). In our example above, the second part of the double entry is to credit your balance sheet with a liability which reflects how you owe the electricity Company £100.

It also works the other way round, for example, if you decrease your expense account (i.e. the electricity Company got it wrong and you actually owe them £80, not £100 as originally thought). We said above that we debit our expenses account when our expenses increase, so the opposite of this is also true i.e. we credit our expenses account when it decreases.

Don’t worry if this is sounding confusing so far – it isn’t a particularly intuitive system to understand at first but I will be going through worked examples and common double entry transactions below. Once you get it though, you won’t forget it and will begin to appreciate how nicely the whole accounting system fits together and why this is important from a financial literacy standpoint.

What is the purpose of Accounting

The definition of Accounting varies depending on who you ask, but generally speaking, it is the process of keeping financial accounts whether that be within a formal business or even on an individual level. The purpose of Accounting is a little more multifaceted – it is designed so that we can record, analyse and summarise the transactions of a business entity to be useful to the ultimate users of that information, whether that be managers, owners, customers, employees or the general public.

Although the process for Accounting varies depending on the size and complexity of the business, the most typical process is that transactions are recorded in the books of original entity, analysed within sub-ledgers and then summarised within the annual financial statements.

Businesses are often required to produce annual financial statements for the benefit of both internal and external stakeholders. For example, management need summarised information on the financial picture of a business to inform how the business will be run going forward. For example, if a business owes a significant amount of money to it’s supplier (known as a ‘trade creditor’), management may be less willing to purchase new stock when they have such a large bill already outstanding.

Similarly, external stakeholders such as prospective investors are also interested in this information – an investor may not wish to invest in a particular business if the financial information suggests that business may not survive going forward. Additionally, those working within the stock market such as brokers and analysts need access to Company’s financial accounts in order to determine whether a Company’s share price is under or overvalued when reviewed against it’s underlying fundamentals (i.e. the information shown on the financial statements)

The purpose of Accounting can basically be boiled down to this – without it, individuals and organisations wouldn’t have the means to record the information they need in order to make good financial decisions.

If Accounting is something you are serious about learning (which it should be) – read my post on Is It Worth Studying Accounting? Everything You Need To Know

The primary financial statements

The three primary financial statements are detailed below but it’s crucial to understand how these are interlinked. The first thing to understand is the below formula:

Assets = Liability + Equity or restated Assets – Liabilities = Equity.

This suggests that net assets (i.e. assets – liabilities) is equal to equity, which makes logical sense. The value of the ownership in the business (the equity) is simply the value of all of the assets minus all of the liabilities of that business where assets are the things owned and the liabilities are the things we owe.

The profit and loss statement

Also known as the income statement, this statement is where all of the revenue (sales) and expenses a business incurs over a period of time is recorded. The most common items you will see on the profit and loss statement are:

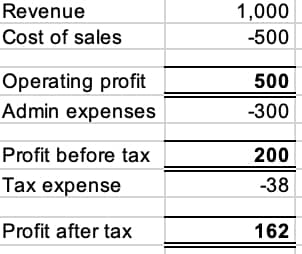

a) Revenue – the cumulative sales recorded in a period. For example, if you sold 100 cakes over the year at £10 each, your revenue would be £1,000.

b) Cost of sales – these are the costs directly attributable to your sales. For example, with cakes, this would include the ingredients and the salary of the bakers. Let’s say this was £5 per cake, your total cost of sales for 100 cakes would therefore be £500 for the year.

c) Operating profit – this is simply a subtotal of the above two items i.e. total revenue minus total cost of sales.

d) Administrative expenses – this includes overheads or other expenses such as utilities. Let’s say all of your administrative expenses for the year are £300.

e) Profit before tax – this is another subtotal of your operating profit minus any other expenses or income (including administrative expenses). Finance income and expenses such as bank charges would typically appear as separate lines between operating profit and profit before tax. Based on our examples above, we would have £200 profit before tax. (£1000 sales -£500 cost of sales -£300 administrative expenses)

f) Tax expense – this is the corporation tax payable to HMRC for the year. In the UK in 2020, this is set at 19% of profit before tax. Meaning our tax expense for the example above would be £200 * 19% = £38.

e) Profit after tax – This is the final subtotal and is simply our profit before tax minus our tax expense. In our running example, this would be £162 (£200 profit before tax – £38 tax expense).

All of this is shown in the example below:

The statement of changes in equity

The next primary financial statement is the statement of changes in equity. This is a fairly straightforward one and simply shows the changes in owners equity year-on-year. For most businesses, this usually comprises just two items.

a) Share capital – this is the ownership of a business represented by the issuance of shares to investors or to the original owners.

b) Retained earnings – this is the cumulative profit (or loss) the business incurs each year. In our example above, £162 would be rolled into this statement and this would be altered by the profit or loss in future years.

The balance sheet

This is the principal financial statement which lays out all of the businesses assets and liabilities as well as the equity which is taken directly from the statement in changes of equity discussed above.

Unlike the profit and loss statement, the balance sheet is not cumulative and is a snapshot at a particular point in time, e.g. 31 December 2019 if that is the Company’s year-end date.

These assets and liabilities are split by current (<12 months) and non-current (>12 months) and common balance sheet captions are:

a) Property, plant and equipment – which is land, buildings, cars and machinery owned by the business.

b) Cash – the cash held in the business’s bank accounts.

c) Accounts receivable – the amounts customers owe you.

d) Accounts payable – the amounts you owe to suppliers or other vendors such as your electricity company.

e) Loans payable – if the business took out any bank loans, the balance would be shown on the balance sheet as a liability (current or non-current dependent on when the loan balance is due).

So how are these financial statements interlinked?

The balance sheet has a section labelled equity which is essentially the capital committed by investors and the cumulative profit earned by the business. This section of the balance sheet is simply the information presented in the statement of changes in equity.

The profit and loss statement is therefore also linked as the final line of this statement “profit after tax” is rolled up into the statement of changes in equity as ‘retained earnings’ which then appears within the equity section of the balance sheet.

Although it’s a bit convoluted to understand without actually looking at a set of accounts, you hopefully by now get the idea of how this neat system of Accounting all fits together.

To see how it works in practice, take a look at a set of Company accounts I have found on companies house here (download the ‘Full accounts made up to 31 December 2018’ PDF for free and see if you can spot the things I’ve mentioned above)

The most common transactions to understand

Now we’ve introduced the concept of DEAD CLIC, what the three primary financial statements are and how they are linked – we can start to see how some of the most common transactions are accounted for using double entry Accounting. For each of the following examples, we will be using our cake shop example from above.

Example 1 – Making a sale

So you’ve sold a cake to a customer for £10 and they have paid you immediately in cash. What is the double entry and impact on the three financial statements?

The double entry is to credit revenue £10 within the profit and loss statement and to debit cash £10 within the balance sheet.

You have increased your income and if we think back to our DEAD CLIC system, we know the following – we have increased our income (sales) and our assets (cash). Increasing our income can be found within the CLIC part of the acronym – (Credit – Liabilities, Income and Capital) whilst increasing our assets (in this case, cash) can be found within the DEAD part of the acronym – (Debit – Expenses, Assets and Drawings).

As you can see, this works with our assets = equity + liability formula. Our assets have been increased by £10 and our equity has also increased by £10 (via retained earnings) so our formula is now £10 = £10 + £0 which balances as it should.

Example 2 – Incurring an expense

So you’ve paid a supplier £2 for all of the ingredients needed to make a cake and you’ve agreed that you will pay the supplier in 30 day times as part of their normal credit terms.

The double entry is debit expenses (cost of sales) £2 within the profit and loss statement and to credit liabilities (via trade payables) £2 within the balance sheet.

Again this follows our DEAD CLIC system, we have increased our expenses so we debit them whilst we have also increased our liabilities (money owed) so we credit this account.

Example 3 – purchasing an industrial baking oven

In this example, we have bought an expensive oven to bake our cakes in. The oven cost £400 and is an example of property, plant and equipment which is typically a non-current asset recorded on the balance sheet.

The double entry is therefore debit PPE (assets) by £400 and credit cash (also an asset) by £400. This example is a bit different from the previous two as both sides of the double entry impact the Balance Sheet and specifically the assets of the business.

This still makes sense with reference to our DEAD CLIC acronym – we increase our assets (we have got a shiny new oven) and as we know, increasing our assets is a debit (Debits – expenses, assets, drawings). However, we have also decreased our assets as we have decreased our cash. As mentioned below, if we decrease our assets, we flip our acronym and instead credit the balance.

The sharp amongst you may be asking ‘why did we expense the baking supplies to the P/L statement and debit expenses but for the oven we have debited assets within the balance sheet?’

The answer is, using the Accounting guidance laid out by Accounting standards, an oven is a ‘capital purchase’ meaning rather than recognising it as an expense as we did with the baking supplies, we can recognise it as an asset as the oven will provide us with benefits in the future.

Conclusion

Broadly speaking, Accounting is the system whereby businesses and individuals record financial transactions in such a way that the information can communicate useful financial information to the ultimate users. The transactions are ultimately recorded in the primary financial statements which are the profit & loss statement, the balance sheet and the statement of changes in equity,

These transactions are typically recorded using the double entry method of bookkeeping where for each transaction, two bookkeeping entries are recorded to different locations on these primary financial statements for example, as revenue on the profit & loss statement and as cash on the balance sheet.

Double entry Accounting operates via debit and credit postings and can be best remembered using the acronym DEAD CLIC. Whereby the debit postings to the accounts includes expenses (to the P&L), assets (to the balance sheet) or drawings (on the statement of changes in equity) and credit postings are liabilities (on the balance sheet), income (on the P&L) and capital (on the statement of changes in equity)

Understanding the basics of Accounting will be straightforward for most people with a bit of practice and understanding the content in the above post is an essential part of financial literacy. Getting to grips with this will help you understand how businesses operate and the fundamentals underpinning your investments into these Companies. Equally as important, it will help you better understand your own financial situation and the steps you need to take to improve it to become financially independent.

For those looking for a greater understanding of Accounting and are considering doing an Accountancy degree, read here for my thoughts on Is an Accounting Degree Worth It in the UK?

If you’ve found yourself interested in Accounting having read this introduction, check out this more thorough guide from the ICAEW linked here.

This article has been written by Luke Girling, ACA – a qualified Accountant and personal finance enthusiast in the UK. Please visit my ‘About‘ page for more information. To get in touch with questions or ideas for future posts, please comment below or contact me here.